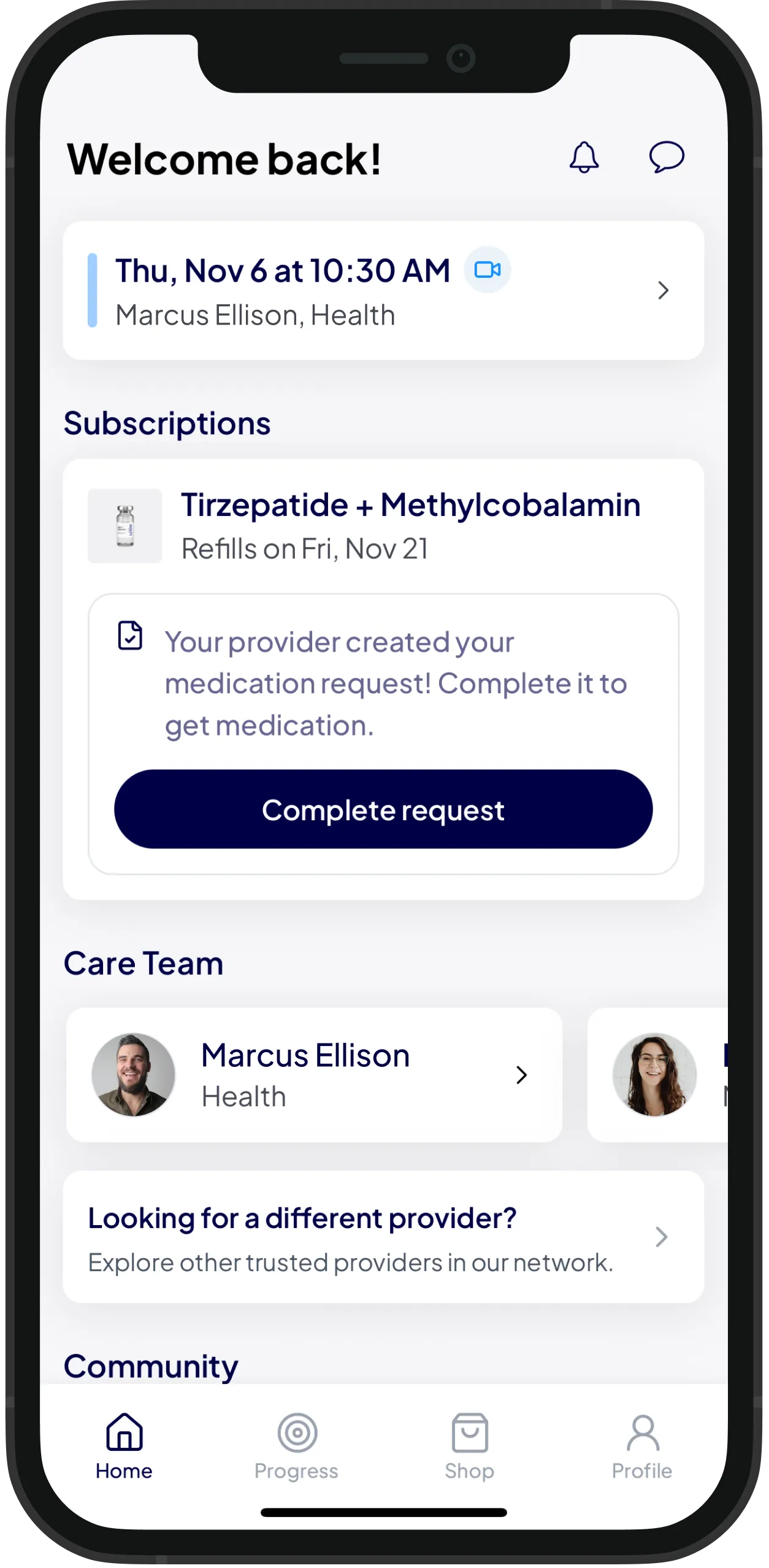

Ready to transform your health?

Unlock access to expert guidance and a weight care plan crafted just for you.

Similar Articles

Similar Articles

GLP-1s for Athletes: Performance, Body Composition, and Recovery

GLP-1s for Athletes: Performance, Body Composition, and Recovery

What Labs Should You Monitor on GLP-1s? A Complete Biomarker Guide

What Labs Should You Monitor on GLP-1s? A Complete Biomarker Guide

Does Semaglutide Affect Fertility or Pregnancy?

Does Semaglutide Affect Fertility or Pregnancy?

How GLP-1s Change Your Gut Microbiome: The Bacteria-Brain-Metabolism Axis

GLP-1 medications like semaglutide and tirzepatide alter gut bacteria composition, improving metabolic health, inflammation, an

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

What The Gut Microbiome Is and Why It Matters

How GLP-1 Medications Affect Gut Bacteria

The Bacteria-Brain-Metabolism Axis

How Gut Bacteria Influence Metabolism

GLP-1s and Gut Barrier Function

Why Some People Respond Better Than Others

How to Support a Healthy Gut Microbiome on GLP-1s

GLP-1s and Digestive Side Effects Through the Microbiome Lens

The Role of Diet Quality in Microbiome Response

What Research Is Still Exploring

Long Term Microbiome Health on GLP-1s

FAQs

References

What The Gut Microbiome Is and Why It Matters

How GLP-1 Medications Affect Gut Bacteria

The Bacteria-Brain-Metabolism Axis

How Gut Bacteria Influence Metabolism

GLP-1s and Gut Barrier Function

Why Some People Respond Better Than Others

How to Support a Healthy Gut Microbiome on GLP-1s

GLP-1s and Digestive Side Effects Through the Microbiome Lens

The Role of Diet Quality in Microbiome Response

What Research Is Still Exploring

Long Term Microbiome Health on GLP-1s

FAQs

References

The gut microbiome has become one of the most studied areas in metabolic health research over the past decade. Trillions of bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms live in your digestive tract and influence everything from digestion and immunity to mood and weight regulation. When the balance of these microbes shifts, it can affect how your body processes food, stores fat, and responds to hunger signals.

GLP-1 medications such as semaglutide and tirzepatide do more than reduce appetite and slow digestion. They also change the composition of gut bacteria in ways that support metabolic health. These changes may explain some of the benefits people experience beyond weight loss, including reduced inflammation, improved insulin sensitivity, and better mood stability. Understanding the connection between GLP-1s, gut bacteria, and metabolism helps explain why these medications work and why some people respond better than others.

This article explores how GLP-1s affect the gut microbiome, what the bacteria-brain-metabolism axis is, how microbiome changes influence weight loss, and what you can do to support a healthy gut during treatment. Everything is written in clear, accessible language based on current research.

If you want to learn whether GLP-1 treatment could support your metabolic health, you can check your eligibility here.

What the Gut Microbiome Is and Why It Matters

Your gut microbiome is the collection of microorganisms that live in your digestive tract, primarily in the large intestine. These bacteria help break down food, produce vitamins, regulate immune function, and communicate with the brain through chemical signals. A healthy microbiome has high diversity, meaning many different types of bacteria coexist in balance.

When the microbiome becomes imbalanced, a condition called dysbiosis, certain harmful bacteria can overgrow while beneficial species decline. Dysbiosis is linked with obesity, type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, inflammation, mood disorders, and digestive problems. People with obesity often have lower microbiome diversity and higher levels of bacteria that promote inflammation and fat storage.

The composition of your gut bacteria influences how efficiently your body extracts energy from food, how much inflammation is present, and how well your metabolism functions. Some bacteria produce short chain fatty acids such as butyrate, which improve insulin sensitivity and reduce inflammation. Other bacteria produce endotoxins that trigger immune responses and worsen metabolic health.

Research shows that people who respond well to weight loss interventions often have healthier baseline microbiomes. This suggests that improving gut bacteria composition may enhance the effectiveness of metabolic treatments, including GLP-1 therapy.

How GLP-1 Medications Affect Gut Bacteria

GLP-1 medications change the gut microbiome in several ways. They slow gastric emptying, which means food stays in the stomach and small intestine longer. This gives bacteria more time to interact with nutrients and affects which types of bacteria thrive. Slower digestion also changes the pH and nutrient availability in the gut, which shifts bacterial populations.

Studies show that GLP-1 therapy increases beneficial bacteria such as Akkermansia muciniphila, which is associated with improved metabolic health, reduced inflammation, and better insulin sensitivity. Akkermansia strengthens the gut barrier, preventing harmful substances from leaking into the bloodstream and triggering inflammation. Higher levels of Akkermansia are consistently found in people with healthier metabolisms.

GLP-1s also increase bacteria that produce short chain fatty acids, including butyrate. Butyrate feeds the cells lining the intestine, reduces inflammation, and improves glucose metabolism. It also influences satiety signals sent to the brain, which may explain why GLP-1 therapy reduces appetite beyond the direct effects of the medication.

Research published in Cell Metabolism found that mice treated with GLP-1 agonists showed increased microbial diversity and higher levels of bacteria associated with leanness. Human studies are still emerging, but early data suggests similar patterns. People on semaglutide or liraglutide show shifts toward bacteria profiles that resemble those of metabolically healthy individuals.

These microbiome changes do not happen overnight. They develop gradually over weeks to months as the medication alters digestive patterns, nutrient availability, and gut environment. This may explain why some benefits of GLP-1 therapy, such as reduced inflammation and improved mood, continue to improve even after weight loss stabilizes.

The Bacteria-Brain-Metabolism Axis

The gut microbiome communicates with the brain through several pathways. Bacteria produce neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and GABA, which influence mood, appetite, and stress responses. They also produce metabolites that travel through the bloodstream and affect brain function. The vagus nerve, which connects the gut to the brain, carries signals in both directions and plays a central role in appetite regulation.

This communication network is called the gut-brain axis. When gut bacteria are balanced, signals sent to the brain support healthy appetite control, stable mood, and appropriate energy use. When bacteria are imbalanced, signals become distorted. The brain may receive exaggerated hunger signals, cravings for unhealthy foods, or reduced satiety after eating.

GLP-1 medications influence this axis by improving bacterial balance and reducing inflammation. Lower inflammation means clearer communication between the gut and brain. Beneficial bacteria produce metabolites that enhance GLP-1 receptor activity in the brain, which strengthens appetite suppression and improves mood stability.

The microbiome also affects how the body responds to GLP-1 therapy. People with healthier baseline microbiomes often experience stronger appetite suppression, better weight loss, and fewer side effects. This suggests that gut health may predict treatment response. Research is exploring whether probiotic interventions or dietary changes before starting GLP-1 therapy could improve outcomes.

How Gut Bacteria Influence Metabolism

Gut bacteria directly affect how the body stores and burns fat. Certain bacteria extract more calories from food, making weight gain easier. Others promote fat burning and improve insulin sensitivity. People with obesity often have higher levels of Firmicutes bacteria and lower levels of Bacteroidetes, a pattern associated with increased energy extraction from food.

Gut bacteria also produce compounds that affect fat storage. Some bacteria trigger the release of hormones that promote fat accumulation. Others produce metabolites that increase fat oxidation and reduce visceral fat. Short chain fatty acids such as butyrate improve mitochondrial function, which helps cells burn energy more efficiently.

Inflammation driven by gut bacteria worsens insulin resistance. When harmful bacteria overgrow, they can damage the intestinal lining, allowing bacterial products to leak into the bloodstream. This triggers immune responses and chronic low grade inflammation, which interferes with insulin signaling and promotes fat storage around the abdomen.

GLP-1 medications help reverse these patterns. By promoting beneficial bacteria and reducing harmful species, they lower inflammation, improve insulin sensitivity, and shift metabolism toward fat burning. These effects work alongside the direct appetite suppressing and glucose regulating actions of the medication.

GLP-1s and Gut Barrier Function

The gut barrier is a single layer of cells that separates the contents of the intestine from the bloodstream. When this barrier is healthy, it allows nutrients to pass through while blocking harmful substances. When the barrier becomes damaged, a condition called leaky gut, bacterial products and toxins can enter the bloodstream and trigger inflammation.

Leaky gut is common in people with obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. It contributes to insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and weight gain. GLP-1 medications help repair the gut barrier by increasing beneficial bacteria such as Akkermansia muciniphila, which produce mucus that protects the intestinal lining.

Improved gut barrier function reduces systemic inflammation, which supports better metabolic health. Many people on GLP-1 therapy notice reduced bloating, more regular digestion, and fewer inflammatory symptoms such as joint pain or skin issues. These changes reflect improvements in gut barrier integrity and lower bacterial translocation into the bloodstream.

Why Some People Respond Better Than Others

Individual differences in gut microbiome composition may explain why some people lose more weight on GLP-1s than others. Research suggests that people with higher baseline levels of Akkermansia muciniphila and other beneficial bacteria respond better to metabolic interventions, including GLP-1 therapy.

Factors that influence baseline microbiome health include diet, antibiotic use, stress, sleep, exercise, and genetics. People who eat high fiber diets, manage stress well, and avoid frequent antibiotic use tend to have healthier microbiomes. Those with history of chronic antibiotic use, high sugar diets, or chronic stress often have lower microbial diversity and poorer treatment responses.

Some researchers are exploring whether testing the microbiome before starting GLP-1 therapy could predict who will respond best. Personalized interventions to improve gut health before treatment might enhance outcomes. This is an emerging area of research, but early findings are promising.

How to Support a Healthy Gut Microbiome on GLP-1s

You can take steps to support gut health during GLP-1 therapy. Eating a variety of fiber rich foods feeds beneficial bacteria. Vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds all provide different types of fiber that support microbial diversity. Aim for at least 25 to 30 grams of fiber per day.

Fermented foods such as yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, and kombucha provide live beneficial bacteria that can colonize the gut. Including these foods regularly supports microbiome health. Look for products labeled with live and active cultures.

Prebiotics are types of fiber that specifically feed beneficial bacteria. Foods high in prebiotics include garlic, onions, leeks, asparagus, bananas, oats, and flaxseeds. Adding these foods to your diet helps beneficial bacteria thrive.

Avoiding unnecessary antibiotics protects microbiome diversity. Antibiotics kill both harmful and beneficial bacteria, which can take months to recover. Use antibiotics only when medically necessary, and consider taking probiotics during and after antibiotic treatment to support recovery.

Managing stress, prioritizing sleep, and staying physically active all support gut health. Chronic stress and poor sleep disrupt the microbiome and increase inflammation. Regular movement promotes microbial diversity and improves gut motility.

Probiotic supplements may help, though the evidence is mixed. Not all probiotics are equally effective, and the best strains for metabolic health are still being studied. If you choose to take a probiotic, look for products with multiple strains, high CFU counts, and third party testing. Discuss with your provider whether a specific probiotic might benefit your situation.

GLP-1s and Digestive Side Effects Through the Microbiome Lens

Many of the digestive side effects people experience on GLP-1 therapy may relate to microbiome changes. As bacteria populations shift, digestion can temporarily become less predictable. Some people experience constipation as beneficial bacteria that support motility adjust to the new environment. Others experience bloating or changes in bowel habits.

These symptoms usually improve as the microbiome stabilizes. Supporting gut health through fiber, hydration, and fermented foods can reduce the intensity and duration of digestive side effects. Probiotics may also help some people, though evidence is still developing.

Severe or persistent digestive symptoms should always be discussed with your provider. While microbiome shifts can cause temporary discomfort, they should not cause severe pain, vomiting, or inability to eat or drink.

The Role of Diet Quality in Microbiome Response

Diet quality influences how well the microbiome responds to GLP-1 therapy. People who eat highly processed foods high in sugar and low in fiber tend to have less favorable microbiome changes. Those who eat whole foods with plenty of fiber, protein, and healthy fats see more pronounced improvements in bacterial diversity and metabolic markers.

GLP-1 medications reduce appetite, which creates an opportunity to prioritize nutrient dense foods. When you eat less, what you do eat matters more. Choosing foods that support gut health amplifies the metabolic benefits of the medication.

This does not mean following a perfect diet. It means making gradual improvements where possible. Adding more vegetables, choosing whole grains over refined grains, including fermented foods, and reducing ultra processed snacks all support a healthier microbiome during treatment.

What Research Is Still Exploring

The connection between GLP-1 medications and the gut microbiome is an active area of research. Scientists are still learning which bacterial species are most important for metabolic health, how quickly microbiome changes occur on GLP-1 therapy, whether microbiome testing can predict treatment response, and whether targeted probiotic or prebiotic interventions can enhance results.

Some researchers are studying whether certain probiotics taken alongside GLP-1 medications could improve weight loss or reduce side effects. Others are exploring whether microbiome analysis before treatment could help personalize dosing or predict who will benefit most.

While these questions are still being answered, the existing evidence clearly shows that GLP-1 medications improve gut bacteria composition in ways that support metabolic health. These changes likely contribute to the long term benefits people experience beyond weight loss.

Long Term Microbiome Health on GLP-1s

Long term GLP-1 use appears to support sustained improvements in gut bacteria composition. Studies following people for one to two years show that beneficial bacteria remain elevated as long as treatment continues. When people stop GLP-1 therapy, some microbiome changes reverse, which may contribute to weight regain.

This suggests that the microbiome benefits of GLP-1 therapy are part of why the medication works and why long term use is often necessary to maintain results. The medication creates an environment where beneficial bacteria thrive, which supports metabolism, reduces inflammation, and helps regulate appetite. When that environment changes, bacteria populations shift again.

Supporting gut health through diet and lifestyle during and after GLP-1 therapy may help maintain some of the microbiome improvements even if treatment is discontinued. However, more research is needed to understand how durable these changes are without medication.

If you want to explore whether GLP-1 therapy could support your metabolic health and gut function, you can check your eligibility here.

FAQs

Do GLP-1 medications change gut bacteria?

Yes. GLP-1s increase beneficial bacteria such as Akkermansia muciniphila and bacteria that produce short chain fatty acids, which improve metabolic health.

How long does it take for the microbiome to change on GLP-1s?

Changes begin within weeks but continue to develop over several months as the gut environment adapts to the medication.

Can I take probiotics with GLP-1 medications?

Yes. Probiotics are generally safe to take with GLP-1s and may help support gut health, though more research is needed on which strains are most beneficial.

Do microbiome changes explain why GLP-1s reduce inflammation?

Partly. Beneficial bacteria produce anti-inflammatory compounds and strengthen the gut barrier, which reduces systemic inflammation.

Will my gut bacteria return to normal if I stop GLP-1s?

Some changes may reverse when treatment stops, which could contribute to weight regain. Supporting gut health through diet may help maintain some benefits.

Check Your Eligibility

If you want to learn whether GLP-1 treatment could support your metabolic health and gut microbiome, you can start by completing Mochi's eligibility questionnaire. It only takes a few minutes and helps our clinical team understand your goals and health history so they can provide personalized guidance. Check your eligibility here.

References

Bauer, P. V., Hamr, S. C., & Duca, F. A. (2016). Regulation of energy balance by a gut-brain axis and involvement of the gut microbiota. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 73(4), 737–755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-015-2083-z

Cani, P. D., & Van Hul, M. (2020). Novel opportunities for next-generation probiotics targeting metabolic syndrome. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 32, 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2014.10.006

Depommier, C., Everard, A., Druart, C., et al. (2019). Supplementation with Akkermansia muciniphila in overweight and obese human volunteers: A proof-of-concept exploratory study. Nature Medicine, 25(7), 1096–1103. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0495-2

Everard, A., Belzer, C., Geurts, L., et al. (2013). Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(22), 9066–9071. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1219451110

Knudsen, L. B., & Lau, J. (2019). The discovery and development of liraglutide and semaglutide. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 10, 155. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00155

Plovier, H., Everard, A., Druart, C., et al. (2017). A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nature Medicine, 23(1), 107–113. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4236

Ryan, P. M., Patterson, E., Carafa, I., et al. (2021). Microbiome and metabolome modifying effects of several cardiovascular disease interventions in apo-E-/- mice. Microbiome, 9(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-020-00980-0

Scheithauer, T. P., Rampanelli, E., Nieuwdorp, M., et al. (2020). Gut microbiota as a trigger for metabolic inflammation in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Frontiers in Immunology, 11, 571731. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.571731

Turnbaugh, P. J., Ley, R. E., Mahowald, M. A., Magrini, V., Mardis, E. R., & Gordon, J. I. (2006). An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature, 444(7122), 1027–1031. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05414

The gut microbiome has become one of the most studied areas in metabolic health research over the past decade. Trillions of bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms live in your digestive tract and influence everything from digestion and immunity to mood and weight regulation. When the balance of these microbes shifts, it can affect how your body processes food, stores fat, and responds to hunger signals.

GLP-1 medications such as semaglutide and tirzepatide do more than reduce appetite and slow digestion. They also change the composition of gut bacteria in ways that support metabolic health. These changes may explain some of the benefits people experience beyond weight loss, including reduced inflammation, improved insulin sensitivity, and better mood stability. Understanding the connection between GLP-1s, gut bacteria, and metabolism helps explain why these medications work and why some people respond better than others.

This article explores how GLP-1s affect the gut microbiome, what the bacteria-brain-metabolism axis is, how microbiome changes influence weight loss, and what you can do to support a healthy gut during treatment. Everything is written in clear, accessible language based on current research.

If you want to learn whether GLP-1 treatment could support your metabolic health, you can check your eligibility here.

What the Gut Microbiome Is and Why It Matters

Your gut microbiome is the collection of microorganisms that live in your digestive tract, primarily in the large intestine. These bacteria help break down food, produce vitamins, regulate immune function, and communicate with the brain through chemical signals. A healthy microbiome has high diversity, meaning many different types of bacteria coexist in balance.

When the microbiome becomes imbalanced, a condition called dysbiosis, certain harmful bacteria can overgrow while beneficial species decline. Dysbiosis is linked with obesity, type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, inflammation, mood disorders, and digestive problems. People with obesity often have lower microbiome diversity and higher levels of bacteria that promote inflammation and fat storage.

The composition of your gut bacteria influences how efficiently your body extracts energy from food, how much inflammation is present, and how well your metabolism functions. Some bacteria produce short chain fatty acids such as butyrate, which improve insulin sensitivity and reduce inflammation. Other bacteria produce endotoxins that trigger immune responses and worsen metabolic health.

Research shows that people who respond well to weight loss interventions often have healthier baseline microbiomes. This suggests that improving gut bacteria composition may enhance the effectiveness of metabolic treatments, including GLP-1 therapy.

How GLP-1 Medications Affect Gut Bacteria

GLP-1 medications change the gut microbiome in several ways. They slow gastric emptying, which means food stays in the stomach and small intestine longer. This gives bacteria more time to interact with nutrients and affects which types of bacteria thrive. Slower digestion also changes the pH and nutrient availability in the gut, which shifts bacterial populations.

Studies show that GLP-1 therapy increases beneficial bacteria such as Akkermansia muciniphila, which is associated with improved metabolic health, reduced inflammation, and better insulin sensitivity. Akkermansia strengthens the gut barrier, preventing harmful substances from leaking into the bloodstream and triggering inflammation. Higher levels of Akkermansia are consistently found in people with healthier metabolisms.

GLP-1s also increase bacteria that produce short chain fatty acids, including butyrate. Butyrate feeds the cells lining the intestine, reduces inflammation, and improves glucose metabolism. It also influences satiety signals sent to the brain, which may explain why GLP-1 therapy reduces appetite beyond the direct effects of the medication.

Research published in Cell Metabolism found that mice treated with GLP-1 agonists showed increased microbial diversity and higher levels of bacteria associated with leanness. Human studies are still emerging, but early data suggests similar patterns. People on semaglutide or liraglutide show shifts toward bacteria profiles that resemble those of metabolically healthy individuals.

These microbiome changes do not happen overnight. They develop gradually over weeks to months as the medication alters digestive patterns, nutrient availability, and gut environment. This may explain why some benefits of GLP-1 therapy, such as reduced inflammation and improved mood, continue to improve even after weight loss stabilizes.

The Bacteria-Brain-Metabolism Axis

The gut microbiome communicates with the brain through several pathways. Bacteria produce neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and GABA, which influence mood, appetite, and stress responses. They also produce metabolites that travel through the bloodstream and affect brain function. The vagus nerve, which connects the gut to the brain, carries signals in both directions and plays a central role in appetite regulation.

This communication network is called the gut-brain axis. When gut bacteria are balanced, signals sent to the brain support healthy appetite control, stable mood, and appropriate energy use. When bacteria are imbalanced, signals become distorted. The brain may receive exaggerated hunger signals, cravings for unhealthy foods, or reduced satiety after eating.

GLP-1 medications influence this axis by improving bacterial balance and reducing inflammation. Lower inflammation means clearer communication between the gut and brain. Beneficial bacteria produce metabolites that enhance GLP-1 receptor activity in the brain, which strengthens appetite suppression and improves mood stability.

The microbiome also affects how the body responds to GLP-1 therapy. People with healthier baseline microbiomes often experience stronger appetite suppression, better weight loss, and fewer side effects. This suggests that gut health may predict treatment response. Research is exploring whether probiotic interventions or dietary changes before starting GLP-1 therapy could improve outcomes.

How Gut Bacteria Influence Metabolism

Gut bacteria directly affect how the body stores and burns fat. Certain bacteria extract more calories from food, making weight gain easier. Others promote fat burning and improve insulin sensitivity. People with obesity often have higher levels of Firmicutes bacteria and lower levels of Bacteroidetes, a pattern associated with increased energy extraction from food.

Gut bacteria also produce compounds that affect fat storage. Some bacteria trigger the release of hormones that promote fat accumulation. Others produce metabolites that increase fat oxidation and reduce visceral fat. Short chain fatty acids such as butyrate improve mitochondrial function, which helps cells burn energy more efficiently.

Inflammation driven by gut bacteria worsens insulin resistance. When harmful bacteria overgrow, they can damage the intestinal lining, allowing bacterial products to leak into the bloodstream. This triggers immune responses and chronic low grade inflammation, which interferes with insulin signaling and promotes fat storage around the abdomen.

GLP-1 medications help reverse these patterns. By promoting beneficial bacteria and reducing harmful species, they lower inflammation, improve insulin sensitivity, and shift metabolism toward fat burning. These effects work alongside the direct appetite suppressing and glucose regulating actions of the medication.

GLP-1s and Gut Barrier Function

The gut barrier is a single layer of cells that separates the contents of the intestine from the bloodstream. When this barrier is healthy, it allows nutrients to pass through while blocking harmful substances. When the barrier becomes damaged, a condition called leaky gut, bacterial products and toxins can enter the bloodstream and trigger inflammation.

Leaky gut is common in people with obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. It contributes to insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and weight gain. GLP-1 medications help repair the gut barrier by increasing beneficial bacteria such as Akkermansia muciniphila, which produce mucus that protects the intestinal lining.

Improved gut barrier function reduces systemic inflammation, which supports better metabolic health. Many people on GLP-1 therapy notice reduced bloating, more regular digestion, and fewer inflammatory symptoms such as joint pain or skin issues. These changes reflect improvements in gut barrier integrity and lower bacterial translocation into the bloodstream.

Why Some People Respond Better Than Others

Individual differences in gut microbiome composition may explain why some people lose more weight on GLP-1s than others. Research suggests that people with higher baseline levels of Akkermansia muciniphila and other beneficial bacteria respond better to metabolic interventions, including GLP-1 therapy.

Factors that influence baseline microbiome health include diet, antibiotic use, stress, sleep, exercise, and genetics. People who eat high fiber diets, manage stress well, and avoid frequent antibiotic use tend to have healthier microbiomes. Those with history of chronic antibiotic use, high sugar diets, or chronic stress often have lower microbial diversity and poorer treatment responses.

Some researchers are exploring whether testing the microbiome before starting GLP-1 therapy could predict who will respond best. Personalized interventions to improve gut health before treatment might enhance outcomes. This is an emerging area of research, but early findings are promising.

How to Support a Healthy Gut Microbiome on GLP-1s

You can take steps to support gut health during GLP-1 therapy. Eating a variety of fiber rich foods feeds beneficial bacteria. Vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds all provide different types of fiber that support microbial diversity. Aim for at least 25 to 30 grams of fiber per day.

Fermented foods such as yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, and kombucha provide live beneficial bacteria that can colonize the gut. Including these foods regularly supports microbiome health. Look for products labeled with live and active cultures.

Prebiotics are types of fiber that specifically feed beneficial bacteria. Foods high in prebiotics include garlic, onions, leeks, asparagus, bananas, oats, and flaxseeds. Adding these foods to your diet helps beneficial bacteria thrive.

Avoiding unnecessary antibiotics protects microbiome diversity. Antibiotics kill both harmful and beneficial bacteria, which can take months to recover. Use antibiotics only when medically necessary, and consider taking probiotics during and after antibiotic treatment to support recovery.

Managing stress, prioritizing sleep, and staying physically active all support gut health. Chronic stress and poor sleep disrupt the microbiome and increase inflammation. Regular movement promotes microbial diversity and improves gut motility.

Probiotic supplements may help, though the evidence is mixed. Not all probiotics are equally effective, and the best strains for metabolic health are still being studied. If you choose to take a probiotic, look for products with multiple strains, high CFU counts, and third party testing. Discuss with your provider whether a specific probiotic might benefit your situation.

GLP-1s and Digestive Side Effects Through the Microbiome Lens

Many of the digestive side effects people experience on GLP-1 therapy may relate to microbiome changes. As bacteria populations shift, digestion can temporarily become less predictable. Some people experience constipation as beneficial bacteria that support motility adjust to the new environment. Others experience bloating or changes in bowel habits.

These symptoms usually improve as the microbiome stabilizes. Supporting gut health through fiber, hydration, and fermented foods can reduce the intensity and duration of digestive side effects. Probiotics may also help some people, though evidence is still developing.

Severe or persistent digestive symptoms should always be discussed with your provider. While microbiome shifts can cause temporary discomfort, they should not cause severe pain, vomiting, or inability to eat or drink.

The Role of Diet Quality in Microbiome Response

Diet quality influences how well the microbiome responds to GLP-1 therapy. People who eat highly processed foods high in sugar and low in fiber tend to have less favorable microbiome changes. Those who eat whole foods with plenty of fiber, protein, and healthy fats see more pronounced improvements in bacterial diversity and metabolic markers.

GLP-1 medications reduce appetite, which creates an opportunity to prioritize nutrient dense foods. When you eat less, what you do eat matters more. Choosing foods that support gut health amplifies the metabolic benefits of the medication.

This does not mean following a perfect diet. It means making gradual improvements where possible. Adding more vegetables, choosing whole grains over refined grains, including fermented foods, and reducing ultra processed snacks all support a healthier microbiome during treatment.

What Research Is Still Exploring

The connection between GLP-1 medications and the gut microbiome is an active area of research. Scientists are still learning which bacterial species are most important for metabolic health, how quickly microbiome changes occur on GLP-1 therapy, whether microbiome testing can predict treatment response, and whether targeted probiotic or prebiotic interventions can enhance results.

Some researchers are studying whether certain probiotics taken alongside GLP-1 medications could improve weight loss or reduce side effects. Others are exploring whether microbiome analysis before treatment could help personalize dosing or predict who will benefit most.

While these questions are still being answered, the existing evidence clearly shows that GLP-1 medications improve gut bacteria composition in ways that support metabolic health. These changes likely contribute to the long term benefits people experience beyond weight loss.

Long Term Microbiome Health on GLP-1s

Long term GLP-1 use appears to support sustained improvements in gut bacteria composition. Studies following people for one to two years show that beneficial bacteria remain elevated as long as treatment continues. When people stop GLP-1 therapy, some microbiome changes reverse, which may contribute to weight regain.

This suggests that the microbiome benefits of GLP-1 therapy are part of why the medication works and why long term use is often necessary to maintain results. The medication creates an environment where beneficial bacteria thrive, which supports metabolism, reduces inflammation, and helps regulate appetite. When that environment changes, bacteria populations shift again.

Supporting gut health through diet and lifestyle during and after GLP-1 therapy may help maintain some of the microbiome improvements even if treatment is discontinued. However, more research is needed to understand how durable these changes are without medication.

If you want to explore whether GLP-1 therapy could support your metabolic health and gut function, you can check your eligibility here.

FAQs

Do GLP-1 medications change gut bacteria?

Yes. GLP-1s increase beneficial bacteria such as Akkermansia muciniphila and bacteria that produce short chain fatty acids, which improve metabolic health.

How long does it take for the microbiome to change on GLP-1s?

Changes begin within weeks but continue to develop over several months as the gut environment adapts to the medication.

Can I take probiotics with GLP-1 medications?

Yes. Probiotics are generally safe to take with GLP-1s and may help support gut health, though more research is needed on which strains are most beneficial.

Do microbiome changes explain why GLP-1s reduce inflammation?

Partly. Beneficial bacteria produce anti-inflammatory compounds and strengthen the gut barrier, which reduces systemic inflammation.

Will my gut bacteria return to normal if I stop GLP-1s?

Some changes may reverse when treatment stops, which could contribute to weight regain. Supporting gut health through diet may help maintain some benefits.

Check Your Eligibility

If you want to learn whether GLP-1 treatment could support your metabolic health and gut microbiome, you can start by completing Mochi's eligibility questionnaire. It only takes a few minutes and helps our clinical team understand your goals and health history so they can provide personalized guidance. Check your eligibility here.

References

Bauer, P. V., Hamr, S. C., & Duca, F. A. (2016). Regulation of energy balance by a gut-brain axis and involvement of the gut microbiota. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 73(4), 737–755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-015-2083-z

Cani, P. D., & Van Hul, M. (2020). Novel opportunities for next-generation probiotics targeting metabolic syndrome. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 32, 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2014.10.006

Depommier, C., Everard, A., Druart, C., et al. (2019). Supplementation with Akkermansia muciniphila in overweight and obese human volunteers: A proof-of-concept exploratory study. Nature Medicine, 25(7), 1096–1103. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0495-2

Everard, A., Belzer, C., Geurts, L., et al. (2013). Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(22), 9066–9071. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1219451110

Knudsen, L. B., & Lau, J. (2019). The discovery and development of liraglutide and semaglutide. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 10, 155. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00155

Plovier, H., Everard, A., Druart, C., et al. (2017). A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nature Medicine, 23(1), 107–113. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4236

Ryan, P. M., Patterson, E., Carafa, I., et al. (2021). Microbiome and metabolome modifying effects of several cardiovascular disease interventions in apo-E-/- mice. Microbiome, 9(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-020-00980-0

Scheithauer, T. P., Rampanelli, E., Nieuwdorp, M., et al. (2020). Gut microbiota as a trigger for metabolic inflammation in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Frontiers in Immunology, 11, 571731. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.571731

Turnbaugh, P. J., Ley, R. E., Mahowald, M. A., Magrini, V., Mardis, E. R., & Gordon, J. I. (2006). An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature, 444(7122), 1027–1031. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05414

Read next

Ready to transform your health?

Unlock access to expert guidance and a weight care plan crafted just for you.

Ready to transform your health?

Unlock access to expert guidance and a weight care plan crafted just for you.

Ready to transform your health?

Unlock access to expert guidance and a weight care plan crafted just for you.

© 2026 Mochi Health

All professional medical services are provided by licensed physicians and clinicians affiliated with independently owned and operated professional practices. Mochi Health Corp. provides administrative and technology services to affiliated medical practices it supports, and does not provide any professional medical services itself.

© 2026 Mochi Health

All professional medical services are provided by licensed physicians and clinicians affiliated with independently owned and operated professional practices. Mochi Health Corp. provides administrative and technology services to affiliated medical practices it supports, and does not provide any professional medical services itself.

© 2026 Mochi Health

All professional medical services are provided by licensed physicians and clinicians affiliated with independently owned and operated professional practices. Mochi Health Corp. provides administrative and technology services to affiliated medical practices it supports, and does not provide any professional medical services itself.