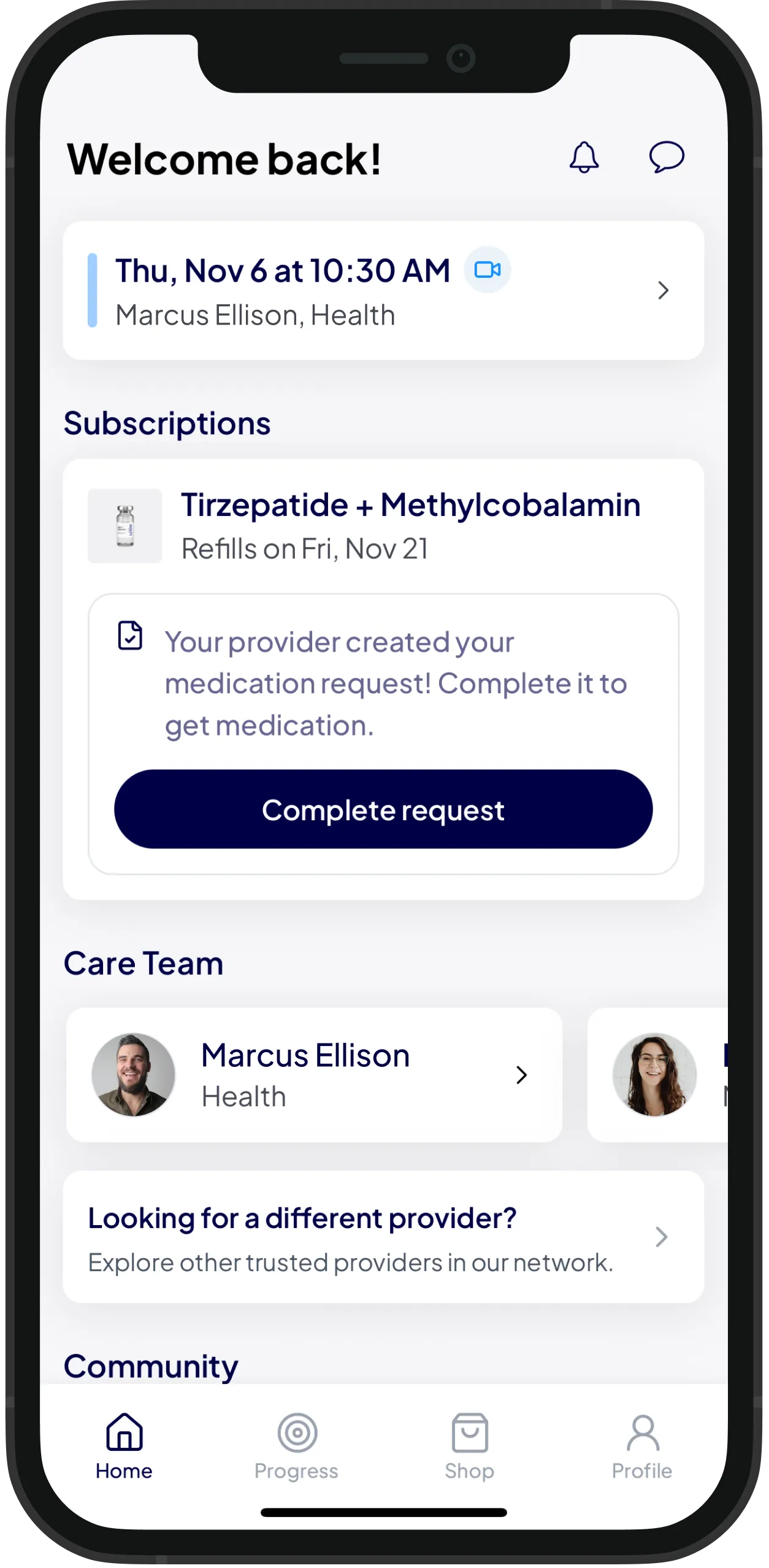

Ready to transform your health?

Unlock access to expert guidance and a weight care plan crafted just for you.

Similar Articles

Similar Articles

GLP-1s for Athletes: Performance, Body Composition, and Recovery

GLP-1s for Athletes: Performance, Body Composition, and Recovery

What Labs Should You Monitor on GLP-1s? A Complete Biomarker Guide

What Labs Should You Monitor on GLP-1s? A Complete Biomarker Guide

Does Semaglutide Affect Fertility or Pregnancy?

Does Semaglutide Affect Fertility or Pregnancy?

Weight, Estrogen, and GLP-1s: Why Women's Plateaus Differ From Men's

Women often experience different weight loss patterns on GLP-1 medications due to estrogen, progesterone, and metabolic differences. Learn why plateaus happen, how hormones affect results, and what you can do.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Why Women Lose Weight Differently Than Men

How Estrogen Affects Metabolism and Weight Loss

Progesterone and Its Role in Plateaus

Why Perimenopausal and Menopausal Women Face unique Challenges

How the Menstrual Cycle Affects GLP-1 Response

Why Women Plateau More Frequently

How GLP-1 Medications Interact With Female Hormones

Strategies to Support Weight Loss During Hormonal Fluctuations

Why Body Composition Matters More Than the Scale

Long Term Outlook for Women on GLP-1 Therapy

FAQs

References

Why Women Lose Weight Differently Than Men

How Estrogen Affects Metabolism and Weight Loss

Progesterone and Its Role in Plateaus

Why Perimenopausal and Menopausal Women Face unique Challenges

How the Menstrual Cycle Affects GLP-1 Response

Why Women Plateau More Frequently

How GLP-1 Medications Interact With Female Hormones

Strategies to Support Weight Loss During Hormonal Fluctuations

Why Body Composition Matters More Than the Scale

Long Term Outlook for Women on GLP-1 Therapy

FAQs

References

Weight loss on GLP-1 medications can look very different for women than it does for men. Women often lose weight more slowly, experience more frequent plateaus, and notice that their results vary significantly throughout their menstrual cycle or during perimenopause. These differences are not about effort or adherence. They reflect fundamental biological differences in how female hormones interact with metabolism, appetite regulation, fat storage, and the mechanisms through which GLP-1 medications work.

Estrogen and progesterone influence insulin sensitivity, leptin signaling, hunger patterns, energy expenditure, and where the body stores fat. When these hormones fluctuate during the menstrual cycle, perimenopause, or menopause, they can create temporary resistance to weight loss even when GLP-1 therapy is working well. Understanding these patterns helps women set realistic expectations, avoid unnecessary frustration, and make adjustments that support long-term success.

If you want to learn whether GLP-1 treatment is appropriate for your metabolism and hormonal profile, you can check your eligibility here. You can also check our list of offerings here.

Why Women Lose Weight Differently Than Men

Men typically lose weight faster on GLP-1 medications. This difference is not due to medication effectiveness but rather to baseline metabolic and hormonal differences. Men generally have higher muscle mass, which increases resting metabolic rate. They also tend to have higher testosterone levels, which support fat oxidation and preserve lean tissue during weight loss.

Women have higher body fat percentages by design. Estrogen promotes fat storage in subcutaneous areas such as the hips, thighs, and breasts. This fat is metabolically protective in many ways, but it is also more resistant to mobilization than visceral fat, which men tend to store more readily. Subcutaneous fat responds more slowly to calorie deficits and requires sustained effort to reduce.

Women also experience cyclical hormonal fluctuations that men do not. Estrogen and progesterone rise and fall throughout the menstrual cycle, influencing water retention, appetite, energy levels, and insulin sensitivity. These shifts can mask fat loss on the scale and create the appearance of stalls even when body composition is improving.

How Estrogen Affects Metabolism and Weight Loss

Estrogen plays a central role in regulating metabolism, fat distribution, and appetite. When estrogen levels are adequate, the hormone improves insulin sensitivity, supports leptin signaling, and helps maintain lean muscle mass. Estrogen also influences where fat is stored, favoring subcutaneous deposits over visceral fat.

During the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, when estrogen is rising, many women feel more energetic, experience better appetite control, and notice that weight loss feels easier. Insulin sensitivity improves, and the body is more responsive to calorie deficits.

However, as estrogen declines during the luteal phase or drops significantly during perimenopause and menopause, several metabolic changes occur. Insulin sensitivity decreases, which can raise fasting insulin levels and promote fat storage. This shift can often lead to a state of hyperinsulinemia, a condition where excess insulin makes burning fat significantly more difficult. Leptin sensitivity may also decline, making hunger signals less reliable. The body shifts toward storing more visceral fat, which is associated with higher inflammation and metabolic risk.

Lower estrogen also affects energy expenditure. Some research suggests that estrogen supports mitochondrial function and thermogenesis. When estrogen declines, resting metabolic rate may decrease slightly, making it harder to maintain a calorie deficit without adjusting intake or activity.

Progesterone and Its Role in Plateaus

Progesterone rises during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, typically in the two weeks before menstruation. While progesterone is essential for reproductive health, it has effects that can interfere with visible weight loss. Progesterone promotes water retention, increases appetite, and may reduce insulin sensitivity slightly.

Many women notice increased hunger, cravings for carbohydrates or sweets, and bloating during this phase. The scale may rise by several pounds due to fluid retention, even if fat loss is continuing. This pattern repeats monthly and can create frustration, especially for women who weigh themselves frequently.

Progesterone also has a mild sedative effect, which can reduce energy levels and make physical activity feel more difficult. These combined effects mean that the luteal phase is often when women feel least confident about their progress, even though metabolic work is still happening beneath the surface.

Why Perimenopausal and Menopausal Women Face Unique Challenges

Perimenopause and menopause introduce even more complexity. Estrogen levels become erratic and eventually decline significantly. Progesterone levels drop as ovulation becomes inconsistent. These hormonal shifts change how the body responds to GLP-1 medications and how weight loss unfolds.

During perimenopause, estrogen fluctuations can cause unpredictable hunger, mood changes, and energy swings. Some weeks may feel easy, while others feel impossible. The body also begins storing more visceral fat, which is more metabolically active and more resistant to loss than subcutaneous fat.

After menopause, when estrogen remains consistently low, metabolism slows further. Lean muscle mass declines more rapidly without the protective effects of estrogen. Insulin resistance often worsens, and inflammation rises. Many women notice that the strategies that worked in their 30s and 40s no longer produce the same results.

GLP-1 medications can still be highly effective during this stage, but expectations must adjust. Weight loss may be slower, and maintaining results requires more attention to protein intake, resistance training, and metabolic support.

How the Menstrual Cycle Affects GLP-1 Response

The menstrual cycle creates a predictable pattern of metabolic shifts that influence how women experience GLP-1 therapy. Understanding this pattern helps women interpret their results more accurately and avoid discouragement during phases when progress feels slower.

During the follicular phase, which begins on the first day of menstruation and lasts about two weeks, estrogen rises steadily. Insulin sensitivity improves, appetite is easier to manage, and energy levels tend to be higher. This is often when women see the most consistent weight loss and feel most in control of their eating.

As ovulation approaches, estrogen peaks. Many women feel their best during this time. Hunger is lower, mood is stable, and the body responds well to calorie deficits.

After ovulation, progesterone rises and estrogen begins to fluctuate. The luteal phase brings increased appetite, cravings, bloating, and water retention. The scale may stall or even rise temporarily. This phase can last up to two weeks and often coincides with feelings of frustration or doubt about whether the medication is working.

When menstruation begins, progesterone and estrogen both drop sharply. Water weight typically sheds quickly, and the scale often drops noticeably within a few days. This is when many women see a "whoosh" effect, where weeks of hidden progress suddenly become visible.

Tracking weight loss across full monthly cycles rather than week to week helps women recognize this pattern and avoid unnecessary concern during the luteal phase.

Why Women Plateau More Frequently

Women experience more frequent plateaus on GLP-1 medications due to hormonal fluctuations, lower baseline metabolic rates, and greater susceptibility to adaptive thermogenesis. Adaptive thermogenesis refers to the body's tendency to slow metabolism in response to calorie restriction. Women's bodies are more sensitive to this response, likely due to evolutionary pressures related to reproduction and energy preservation.

When calorie intake decreases, the body reduces energy expenditure by lowering non-exercise activity thermogenesis, or NEAT, reducing thyroid hormone conversion, and downregulating metabolic processes. Women experience this effect more strongly than men, which means that even with consistent GLP-1 therapy, weight loss can slow or stop temporarily.

Plateaus are also more common during the luteal phase, perimenopause, and periods of high stress. Cortisol, the stress hormone, interacts with estrogen and progesterone to influence insulin sensitivity and fat storage. Chronic stress combined with hormonal fluctuations creates a metabolic environment where weight loss becomes more difficult.

Sleep deprivation worsens this effect. Poor sleep raises cortisol, lowers leptin sensitivity, and increases ghrelin, the hunger hormone. Women who are perimenopausal or experiencing hormonal shifts often have disrupted sleep, which compounds the metabolic challenges they already face.

How GLP-1 Medications Interact With Female Hormones

GLP-1 medications work by mimicking a natural gut hormone that regulates blood sugar, slows gastric emptying, and reduces appetite. These effects are powerful regardless of sex, but the way they interact with female hormones creates some unique patterns.

GLP-1s improve insulin sensitivity, which can help counteract the insulin resistance that worsens during the luteal phase and after menopause. By stabilizing blood sugar and reducing insulin spikes, GLP-1s make it easier to maintain a calorie deficit even when hormones would otherwise increase hunger.

However, GLP-1s do not override all hormonal signals. Women may still experience increased appetite during the luteal phase or perimenopausal hormone surges. The medication reduces the intensity of these signals but does not eliminate them entirely. This is why some women find that they need slightly higher doses during certain phases of their cycle or during perimenopause to maintain the same level of appetite control.

GLP-1 medications also reduce inflammation, which improves leptin sensitivity. Since estrogen decline is associated with increased inflammation, this effect may be especially beneficial for perimenopausal and menopausal women. Lower inflammation supports better communication between fat tissue and the brain, helping hunger signals become more reliable.

Strategies to Support Weight Loss During Hormonal Fluctuations

Women can take several steps to support consistent progress even when hormones create temporary resistance. These strategies do not eliminate hormonal effects, but they reduce their impact and help maintain momentum through difficult phases.

Tracking weight across full menstrual cycles rather than weekly helps women see patterns and avoid reacting to temporary fluctuations. Weighing daily and looking at monthly trends often provides more clarity than weekly weigh-ins, which may fall during the luteal phase and create false impressions of stalling.

Increasing protein intake during the luteal phase helps manage hunger and preserve lean muscle mass. Protein has the highest thermic effect of all macronutrients, meaning the body burns more calories digesting it. Protein also supports satiety and reduces cravings, which are often stronger during this phase.

Resistance training becomes even more important for women, especially during perimenopause and menopause. Maintaining or building lean muscle mass supports metabolic rate and counteracts the natural decline in muscle that occurs when estrogen drops. Strength training also improves insulin sensitivity and supports long-term weight maintenance.

Prioritizing sleep and managing stress are essential. Both influence cortisol levels, which interact with estrogen and progesterone to affect metabolism. Women who improve sleep quality and incorporate stress reduction practices often see better and more consistent results.

Some women find that adjusting their GLP-1 dose slightly during the luteal phase or during perimenopause helps maintain appetite control. This should always be done in consultation with a healthcare provider, but small adjustments can make hormonal phases more manageable.

Why Body Composition Matters More Than the Scale

For women, body composition changes often outpace scale changes, especially during hormonal fluctuations. Fat loss may continue while water retention masks progress. Lean muscle may increase through resistance training, which improves metabolism but does not always show up as lower numbers on the scale.

Tracking measurements, progress photos, and how clothing fits provides a more accurate picture of progress than the scale alone. Many women find that they lose inches even during weeks when the scale does not move. This is especially common during the luteal phase and during perimenopause.

Body composition changes are also more predictive of health outcomes than weight alone. Losing visceral fat, preserving muscle mass, and improving insulin sensitivity are all metabolically beneficial even if the scale moves slowly.

Long-Term Outlook for Women on GLP-1 Therapy

Women can achieve significant and sustained weight loss on GLP-1 medications, but the timeline may be longer. Hormonal fluctuations create temporary obstacles, but they do not prevent progress.

GLP-1 therapy combined with adequate protein intake, resistance training, and attention to sleep and stress creates a strong foundation for metabolic improvement. Over time, insulin sensitivity improves, inflammation decreases, and appetite regulation becomes more stable. Many women find that even though weight loss feels slow, the cumulative effect over months is noticeable.

For perimenopausal and menopausal women, GLP-1 therapy offers particular benefits. By improving insulin sensitivity and reducing visceral fat, these medications help counteract some of the metabolic changes that occur when estrogen declines. This can improve not only weight but also cardiovascular health, energy levels, and overall quality of life.

If you want to see whether GLP-1 treatment fits your metabolic and hormonal profile, you can check your eligibility here.

FAQs

Why do I gain weight during my period even on GLP-1s?

Progesterone causes water retention during the luteal phase and early menstruation. This is temporary and does not reflect fat gain. Weight typically drops after menstruation begins.

Do I need a higher GLP-1 dose during perimenopause?

Some women find that appetite control becomes more challenging during perimenopause. Dose adjustments may help, but this should be discussed with your healthcare provider.

Can GLP-1s help with menopause-related weight gain?

Yes. GLP-1s improve insulin sensitivity and reduce visceral fat, both of which are affected by estrogen decline. Many menopausal women respond well to GLP-1 therapy.

Should I track my weight daily or weekly?

Daily tracking with a focus on monthly trends often works better for women because it reveals cyclical patterns that weekly weigh-ins can miss.

Is it normal to plateau during the second half of my cycle?

Yes. Progesterone-related water retention and increased appetite often slow visible progress during the luteal phase. This is a normal hormonal pattern, not a treatment failure.

Check Your Eligibility

If you want to learn whether GLP-1 treatment could help support your weight loss goals while accounting for your hormonal patterns, you can start by completing Mochi's eligibility questionnaire. It only takes a few minutes and helps our clinical team understand your goals and health history so they can provide personalized guidance. Check your eligibility here.

References

Carr, M. C. (2003). The emergence of the metabolic syndrome with menopause. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 88(6), 2404–2411. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2003-030242

Daka, B., Rosen, T., Jansson, P. A., Råstam, L., Larsson, C. A., & Lindblad, U. (2015). Inverse association between serum insulin and sex hormone-binding globulin in a population survey in Sweden. Endocrine Connections, 4(3), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1530/EC-15-0017

Jastreboff, A. M., Aronne, L. J., Ahmad, N. N., Wharton, S., Connery, L., Alves, B., Kiyosue, A., Zhang, S., Liu, B., Bunck, M. C., Stefanski, A., & SURMOUNT-1 Investigators. (2022). Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. New England Journal of Medicine, 387(3), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2206038

Lovejoy, J. C., Champagne, C. M., de Jonge, L., Xie, H., & Smith, S. R. (2008). Increased visceral fat and decreased energy expenditure during the menopausal transition. International Journal of Obesity, 32(6), 949–958. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.25

Marlatt, K. L., Pitynski-Miller, D. R., Gavin, K. M., Moreau, K. L., Melanson, E. L., Santoro, N., & Kohrt, W. M. (2022). Body composition and cardiometabolic health across the menopause transition. Obesity, 30(1), 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23289

Pastore, I., Bolla, A. M., Montefusco, L., Lunati, M. E., Rossi, A., Assi, E., Zuccotti, G. V., & Fiorina, P. (2021). The impact of diabetes mellitus on cardiovascular risk onset in women: A women-specific overview. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(9), 4656. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22094656

Pepino, M. Y., Kuda, O., Samovski, D., & Abumrad, N. A. (2014). Structure-function of CD36 and importance of fatty acid signal transduction in fat metabolism. Annual Review of Nutrition, 34, 281–303. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-071812-161220

Wilding, J. P. H., Batterham, R. L., Calanna, S., Davies, M., Van Gaal, L. F., Lingvay, I., McGowan, B. M., Rosenstock, J., Tran, M. T. D., Wadden, T. A., Wharton, S., Yokote, K., Zeuthen, N., Kushner, R. F., & STEP 1 Study Group. (2021). Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(11), 989–1002. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2032183

Zore, T., Palafox, M., & Reue, K. (2018). Sex differences in obesity, lipid metabolism, and inflammation—A role for the sex chromosomes? Molecular Metabolism, 15, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2018.04.003

Retry

Turn on web search in Search and tools menu. Otherwise, links provided may not be accurate or up to date.

Weight loss on GLP-1 medications can look very different for women than it does for men. Women often lose weight more slowly, experience more frequent plateaus, and notice that their results vary significantly throughout their menstrual cycle or during perimenopause. These differences are not about effort or adherence. They reflect fundamental biological differences in how female hormones interact with metabolism, appetite regulation, fat storage, and the mechanisms through which GLP-1 medications work.

Estrogen and progesterone influence insulin sensitivity, leptin signaling, hunger patterns, energy expenditure, and where the body stores fat. When these hormones fluctuate during the menstrual cycle, perimenopause, or menopause, they can create temporary resistance to weight loss even when GLP-1 therapy is working well. Understanding these patterns helps women set realistic expectations, avoid unnecessary frustration, and make adjustments that support long-term success.

If you want to learn whether GLP-1 treatment is appropriate for your metabolism and hormonal profile, you can check your eligibility here. You can also check our list of offerings here.

Why Women Lose Weight Differently Than Men

Men typically lose weight faster on GLP-1 medications. This difference is not due to medication effectiveness but rather to baseline metabolic and hormonal differences. Men generally have higher muscle mass, which increases resting metabolic rate. They also tend to have higher testosterone levels, which support fat oxidation and preserve lean tissue during weight loss.

Women have higher body fat percentages by design. Estrogen promotes fat storage in subcutaneous areas such as the hips, thighs, and breasts. This fat is metabolically protective in many ways, but it is also more resistant to mobilization than visceral fat, which men tend to store more readily. Subcutaneous fat responds more slowly to calorie deficits and requires sustained effort to reduce.

Women also experience cyclical hormonal fluctuations that men do not. Estrogen and progesterone rise and fall throughout the menstrual cycle, influencing water retention, appetite, energy levels, and insulin sensitivity. These shifts can mask fat loss on the scale and create the appearance of stalls even when body composition is improving.

How Estrogen Affects Metabolism and Weight Loss

Estrogen plays a central role in regulating metabolism, fat distribution, and appetite. When estrogen levels are adequate, the hormone improves insulin sensitivity, supports leptin signaling, and helps maintain lean muscle mass. Estrogen also influences where fat is stored, favoring subcutaneous deposits over visceral fat.

During the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, when estrogen is rising, many women feel more energetic, experience better appetite control, and notice that weight loss feels easier. Insulin sensitivity improves, and the body is more responsive to calorie deficits.

However, as estrogen declines during the luteal phase or drops significantly during perimenopause and menopause, several metabolic changes occur. Insulin sensitivity decreases, which can raise fasting insulin levels and promote fat storage. This shift can often lead to a state of hyperinsulinemia, a condition where excess insulin makes burning fat significantly more difficult. Leptin sensitivity may also decline, making hunger signals less reliable. The body shifts toward storing more visceral fat, which is associated with higher inflammation and metabolic risk.

Lower estrogen also affects energy expenditure. Some research suggests that estrogen supports mitochondrial function and thermogenesis. When estrogen declines, resting metabolic rate may decrease slightly, making it harder to maintain a calorie deficit without adjusting intake or activity.

Progesterone and Its Role in Plateaus

Progesterone rises during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, typically in the two weeks before menstruation. While progesterone is essential for reproductive health, it has effects that can interfere with visible weight loss. Progesterone promotes water retention, increases appetite, and may reduce insulin sensitivity slightly.

Many women notice increased hunger, cravings for carbohydrates or sweets, and bloating during this phase. The scale may rise by several pounds due to fluid retention, even if fat loss is continuing. This pattern repeats monthly and can create frustration, especially for women who weigh themselves frequently.

Progesterone also has a mild sedative effect, which can reduce energy levels and make physical activity feel more difficult. These combined effects mean that the luteal phase is often when women feel least confident about their progress, even though metabolic work is still happening beneath the surface.

Why Perimenopausal and Menopausal Women Face Unique Challenges

Perimenopause and menopause introduce even more complexity. Estrogen levels become erratic and eventually decline significantly. Progesterone levels drop as ovulation becomes inconsistent. These hormonal shifts change how the body responds to GLP-1 medications and how weight loss unfolds.

During perimenopause, estrogen fluctuations can cause unpredictable hunger, mood changes, and energy swings. Some weeks may feel easy, while others feel impossible. The body also begins storing more visceral fat, which is more metabolically active and more resistant to loss than subcutaneous fat.

After menopause, when estrogen remains consistently low, metabolism slows further. Lean muscle mass declines more rapidly without the protective effects of estrogen. Insulin resistance often worsens, and inflammation rises. Many women notice that the strategies that worked in their 30s and 40s no longer produce the same results.

GLP-1 medications can still be highly effective during this stage, but expectations must adjust. Weight loss may be slower, and maintaining results requires more attention to protein intake, resistance training, and metabolic support.

How the Menstrual Cycle Affects GLP-1 Response

The menstrual cycle creates a predictable pattern of metabolic shifts that influence how women experience GLP-1 therapy. Understanding this pattern helps women interpret their results more accurately and avoid discouragement during phases when progress feels slower.

During the follicular phase, which begins on the first day of menstruation and lasts about two weeks, estrogen rises steadily. Insulin sensitivity improves, appetite is easier to manage, and energy levels tend to be higher. This is often when women see the most consistent weight loss and feel most in control of their eating.

As ovulation approaches, estrogen peaks. Many women feel their best during this time. Hunger is lower, mood is stable, and the body responds well to calorie deficits.

After ovulation, progesterone rises and estrogen begins to fluctuate. The luteal phase brings increased appetite, cravings, bloating, and water retention. The scale may stall or even rise temporarily. This phase can last up to two weeks and often coincides with feelings of frustration or doubt about whether the medication is working.

When menstruation begins, progesterone and estrogen both drop sharply. Water weight typically sheds quickly, and the scale often drops noticeably within a few days. This is when many women see a "whoosh" effect, where weeks of hidden progress suddenly become visible.

Tracking weight loss across full monthly cycles rather than week to week helps women recognize this pattern and avoid unnecessary concern during the luteal phase.

Why Women Plateau More Frequently

Women experience more frequent plateaus on GLP-1 medications due to hormonal fluctuations, lower baseline metabolic rates, and greater susceptibility to adaptive thermogenesis. Adaptive thermogenesis refers to the body's tendency to slow metabolism in response to calorie restriction. Women's bodies are more sensitive to this response, likely due to evolutionary pressures related to reproduction and energy preservation.

When calorie intake decreases, the body reduces energy expenditure by lowering non-exercise activity thermogenesis, or NEAT, reducing thyroid hormone conversion, and downregulating metabolic processes. Women experience this effect more strongly than men, which means that even with consistent GLP-1 therapy, weight loss can slow or stop temporarily.

Plateaus are also more common during the luteal phase, perimenopause, and periods of high stress. Cortisol, the stress hormone, interacts with estrogen and progesterone to influence insulin sensitivity and fat storage. Chronic stress combined with hormonal fluctuations creates a metabolic environment where weight loss becomes more difficult.

Sleep deprivation worsens this effect. Poor sleep raises cortisol, lowers leptin sensitivity, and increases ghrelin, the hunger hormone. Women who are perimenopausal or experiencing hormonal shifts often have disrupted sleep, which compounds the metabolic challenges they already face.

How GLP-1 Medications Interact With Female Hormones

GLP-1 medications work by mimicking a natural gut hormone that regulates blood sugar, slows gastric emptying, and reduces appetite. These effects are powerful regardless of sex, but the way they interact with female hormones creates some unique patterns.

GLP-1s improve insulin sensitivity, which can help counteract the insulin resistance that worsens during the luteal phase and after menopause. By stabilizing blood sugar and reducing insulin spikes, GLP-1s make it easier to maintain a calorie deficit even when hormones would otherwise increase hunger.

However, GLP-1s do not override all hormonal signals. Women may still experience increased appetite during the luteal phase or perimenopausal hormone surges. The medication reduces the intensity of these signals but does not eliminate them entirely. This is why some women find that they need slightly higher doses during certain phases of their cycle or during perimenopause to maintain the same level of appetite control.

GLP-1 medications also reduce inflammation, which improves leptin sensitivity. Since estrogen decline is associated with increased inflammation, this effect may be especially beneficial for perimenopausal and menopausal women. Lower inflammation supports better communication between fat tissue and the brain, helping hunger signals become more reliable.

Strategies to Support Weight Loss During Hormonal Fluctuations

Women can take several steps to support consistent progress even when hormones create temporary resistance. These strategies do not eliminate hormonal effects, but they reduce their impact and help maintain momentum through difficult phases.

Tracking weight across full menstrual cycles rather than weekly helps women see patterns and avoid reacting to temporary fluctuations. Weighing daily and looking at monthly trends often provides more clarity than weekly weigh-ins, which may fall during the luteal phase and create false impressions of stalling.

Increasing protein intake during the luteal phase helps manage hunger and preserve lean muscle mass. Protein has the highest thermic effect of all macronutrients, meaning the body burns more calories digesting it. Protein also supports satiety and reduces cravings, which are often stronger during this phase.

Resistance training becomes even more important for women, especially during perimenopause and menopause. Maintaining or building lean muscle mass supports metabolic rate and counteracts the natural decline in muscle that occurs when estrogen drops. Strength training also improves insulin sensitivity and supports long-term weight maintenance.

Prioritizing sleep and managing stress are essential. Both influence cortisol levels, which interact with estrogen and progesterone to affect metabolism. Women who improve sleep quality and incorporate stress reduction practices often see better and more consistent results.

Some women find that adjusting their GLP-1 dose slightly during the luteal phase or during perimenopause helps maintain appetite control. This should always be done in consultation with a healthcare provider, but small adjustments can make hormonal phases more manageable.

Why Body Composition Matters More Than the Scale

For women, body composition changes often outpace scale changes, especially during hormonal fluctuations. Fat loss may continue while water retention masks progress. Lean muscle may increase through resistance training, which improves metabolism but does not always show up as lower numbers on the scale.

Tracking measurements, progress photos, and how clothing fits provides a more accurate picture of progress than the scale alone. Many women find that they lose inches even during weeks when the scale does not move. This is especially common during the luteal phase and during perimenopause.

Body composition changes are also more predictive of health outcomes than weight alone. Losing visceral fat, preserving muscle mass, and improving insulin sensitivity are all metabolically beneficial even if the scale moves slowly.

Long-Term Outlook for Women on GLP-1 Therapy

Women can achieve significant and sustained weight loss on GLP-1 medications, but the timeline may be longer. Hormonal fluctuations create temporary obstacles, but they do not prevent progress.

GLP-1 therapy combined with adequate protein intake, resistance training, and attention to sleep and stress creates a strong foundation for metabolic improvement. Over time, insulin sensitivity improves, inflammation decreases, and appetite regulation becomes more stable. Many women find that even though weight loss feels slow, the cumulative effect over months is noticeable.

For perimenopausal and menopausal women, GLP-1 therapy offers particular benefits. By improving insulin sensitivity and reducing visceral fat, these medications help counteract some of the metabolic changes that occur when estrogen declines. This can improve not only weight but also cardiovascular health, energy levels, and overall quality of life.

If you want to see whether GLP-1 treatment fits your metabolic and hormonal profile, you can check your eligibility here.

FAQs

Why do I gain weight during my period even on GLP-1s?

Progesterone causes water retention during the luteal phase and early menstruation. This is temporary and does not reflect fat gain. Weight typically drops after menstruation begins.

Do I need a higher GLP-1 dose during perimenopause?

Some women find that appetite control becomes more challenging during perimenopause. Dose adjustments may help, but this should be discussed with your healthcare provider.

Can GLP-1s help with menopause-related weight gain?

Yes. GLP-1s improve insulin sensitivity and reduce visceral fat, both of which are affected by estrogen decline. Many menopausal women respond well to GLP-1 therapy.

Should I track my weight daily or weekly?

Daily tracking with a focus on monthly trends often works better for women because it reveals cyclical patterns that weekly weigh-ins can miss.

Is it normal to plateau during the second half of my cycle?

Yes. Progesterone-related water retention and increased appetite often slow visible progress during the luteal phase. This is a normal hormonal pattern, not a treatment failure.

Check Your Eligibility

If you want to learn whether GLP-1 treatment could help support your weight loss goals while accounting for your hormonal patterns, you can start by completing Mochi's eligibility questionnaire. It only takes a few minutes and helps our clinical team understand your goals and health history so they can provide personalized guidance. Check your eligibility here.

References

Carr, M. C. (2003). The emergence of the metabolic syndrome with menopause. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 88(6), 2404–2411. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2003-030242

Daka, B., Rosen, T., Jansson, P. A., Råstam, L., Larsson, C. A., & Lindblad, U. (2015). Inverse association between serum insulin and sex hormone-binding globulin in a population survey in Sweden. Endocrine Connections, 4(3), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1530/EC-15-0017

Jastreboff, A. M., Aronne, L. J., Ahmad, N. N., Wharton, S., Connery, L., Alves, B., Kiyosue, A., Zhang, S., Liu, B., Bunck, M. C., Stefanski, A., & SURMOUNT-1 Investigators. (2022). Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. New England Journal of Medicine, 387(3), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2206038

Lovejoy, J. C., Champagne, C. M., de Jonge, L., Xie, H., & Smith, S. R. (2008). Increased visceral fat and decreased energy expenditure during the menopausal transition. International Journal of Obesity, 32(6), 949–958. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.25

Marlatt, K. L., Pitynski-Miller, D. R., Gavin, K. M., Moreau, K. L., Melanson, E. L., Santoro, N., & Kohrt, W. M. (2022). Body composition and cardiometabolic health across the menopause transition. Obesity, 30(1), 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23289

Pastore, I., Bolla, A. M., Montefusco, L., Lunati, M. E., Rossi, A., Assi, E., Zuccotti, G. V., & Fiorina, P. (2021). The impact of diabetes mellitus on cardiovascular risk onset in women: A women-specific overview. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(9), 4656. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22094656

Pepino, M. Y., Kuda, O., Samovski, D., & Abumrad, N. A. (2014). Structure-function of CD36 and importance of fatty acid signal transduction in fat metabolism. Annual Review of Nutrition, 34, 281–303. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-071812-161220

Wilding, J. P. H., Batterham, R. L., Calanna, S., Davies, M., Van Gaal, L. F., Lingvay, I., McGowan, B. M., Rosenstock, J., Tran, M. T. D., Wadden, T. A., Wharton, S., Yokote, K., Zeuthen, N., Kushner, R. F., & STEP 1 Study Group. (2021). Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(11), 989–1002. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2032183

Zore, T., Palafox, M., & Reue, K. (2018). Sex differences in obesity, lipid metabolism, and inflammation—A role for the sex chromosomes? Molecular Metabolism, 15, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2018.04.003

Retry

Turn on web search in Search and tools menu. Otherwise, links provided may not be accurate or up to date.

Read next

Ready to transform your health?

Unlock access to expert guidance and a weight care plan crafted just for you.

Ready to transform your health?

Unlock access to expert guidance and a weight care plan crafted just for you.

Ready to transform your health?

Unlock access to expert guidance and a weight care plan crafted just for you.

© 2026 Mochi Health

All professional medical services are provided by licensed physicians and clinicians affiliated with independently owned and operated professional practices. Mochi Health Corp. provides administrative and technology services to affiliated medical practices it supports, and does not provide any professional medical services itself.

© 2026 Mochi Health

All professional medical services are provided by licensed physicians and clinicians affiliated with independently owned and operated professional practices. Mochi Health Corp. provides administrative and technology services to affiliated medical practices it supports, and does not provide any professional medical services itself.

© 2026 Mochi Health

All professional medical services are provided by licensed physicians and clinicians affiliated with independently owned and operated professional practices. Mochi Health Corp. provides administrative and technology services to affiliated medical practices it supports, and does not provide any professional medical services itself.